The Art Spirit By Robert Henri

Chapter 5

The Art Spirit

Robert Henri

Chapter 5

The Brush Stroke

The picture that looks as if it were done without an effort

Originality

An address to the students of the School of Design for Women, Philadelphia (1901)

1.

The Brush Stroke

The mere matter of putting on paint.

The power of a brush stroke.

There is a certain kind of brush stroke that is both bold and bad.

There are timid, halting brush strokes.

Strokes that started bravely but don’t know where to go. Sometimes they bump into and spoil something else, or they may just wander about, or fade into doubtfulness.

There are strokes in the background which come up against the head and turn to get out of the way.

Strokes which look like brush strokes and bring us back to paint.

There are other strokes which inspire a sense of vigor, direction, speed, fullness and all the varying sensations an artist may wish to express.

The mere brush stroke itself must speak. It counts whether you will or not. It is meaningful or it is empty. It is on the canvas and it tells its tale. It is showy, shallow, mean, meagre, selfish, has the skimp of a miser; is rich, full, generous, alive and knows what is going on.

When the brush stroke is visible on the canvas it has a size, covers a certain area, has its own texture. Its tiny but very expressive ridges catch light in their own way. It has its speed and its direction. There is a lot it has of itself, and the strokes tell their tale in harmony with or in opposition to the motive of the picture.

On account of the shiny character of paint it is necessary to adhere to a general movement in brush direction to avoid a stroke which will shine even though the picture hangs in its proper light.

It sometimes happens that drawing dictates a sweep in a certain direction while to avoid the “shine” the opposite direction must be taken. Here is where one’s ingenuity and skill is brought into play. It is like walking well walking backward. It’s a feat one has to accomplish.

We often hear, “If somebody would only invent an oil paint that would not shine!” Few want to give up oil paint, but all have distressing moments over the technical avoidances of a destroying shine.

Sometimes the stroke may be made in the direction drawing dictates, and the shine can be killed by a very delicate and skillful blending stroke with a clean brush; thus breaking down the light-catching ridges of the original strokes. This is difficult to accomplish without a resultant weakening or softening of the original stroke.

Sometimes this blending or flattening stroke can be made at once. Other times better to do it later when the paint is more set.

In this latter case where the shine is not removed at once the artist will be bothered by the falseness of the note, due to the presence of the reflected light, and he will be much troubled, for he must consider it as it is to appear when flattened, not as it is with the shine on it, and he must work accordingly.

There are few outsiders who have any dream of the difficulties an artist has to meet in the mere putting on of his paint.

There are strokes which depress whole canvases with a down-grade movement and a down-grade feeling as a result.

Some backgrounds which should give a rising sense seep downward with thin paint and strokes which seem to be weeping.

There are the attenuated strokes.

Strokes which seem to stretch the paint in an effort to make it cover.

Miserly strokes.

There are rich, fluent, abundant strokes.

Strokes that come from brushes which seem full charged, as though they were filled to the hilt and had plenty to give.

Strokes which mount, carry up, rise. See Greco’s pictures.

Strokes which are placid.

An evening scene by Hiroshigi. The horizontal.

The stroke of the eyebrow as it rises in surprise.

A stroke in the ear which connects with the activities of the other features.

A stroke which gives the indolence, voluptuousness, caress, fullness, illusiveness, vital energy, vigor, rest and flow of hair.

Strokes which end too soon.

Dull strokes and confused strokes on youthful, spirited faces.

The stroke of highlight in the eye. Much meaning in whether it is horizontal, pointing up, pointing down, or high or low on the pupil.

Bad strokes which are bad because a brush or condition of paint was chosen which could not render them.

For things which require a greater steadiness of hand than you can command, use a maul stick.

Strokes carry a message whether you will it or not. The stroke is just like the artist at the time he makes it. All the certainties, all the uncertainties, all the bigness of his spirit and all the littlenesses are in it.

Look at the stroke of a Chinese master. Sung period. There are strokes which comprehend a shape.

There are strokes which are doubtful of shape.

The stroke which marks the path of a rocket into the sky may be only a few inches long, but the spirit of the artist has traveled a thousand feet at the moment he made that stroke.

There are whole canvases that are but a multitude of parsimonious, mean little touches.

There are strokes which laugh, and there are strokes which bind laughter, which freeze the face into a set immovable grimace.

Strokes which carry the observer with exact degrees of speed.

Strokes which increase their speed, or decrease it.

Strokes with one sharp defining edge carrying on its other side its complement, soft, merging.

It is wonderful how much steadiness can be commanded by will, by intense desire.

Use a maul stick—use anything when you have to. Don’t use them except when you have to.

If possible, transmit through your free body and hand.

Whatever feeling, whatever state you have at the time of the stroke will register in the stroke.

Many a canvas carries on its face the artist’s thought of the cost of paint. And many a picture has fallen short of its original intention by the obtrusion of this idea.

It is not necessarily the poor who think of the cost of paint. Many an artist has starved his stomach and remained a spendthrift in paint.

The reverse is also true.

Strokes with too much or too little medium.

The stroke in itself; in its own texture, that is, the texture it has of itself apart from the texture it is intended to reproduce, is a thing on the canvas, is an idea in itself, and it must correlate with the ideas of the picture.

The stroke may make or it may destroy the integrity of the forms.

There is a fine substance to flesh. “Just any kind” of a stroke won’t render it.

A brush may be charged with more than one color and the single stroke may render a complete form in very wonderful variation and blend of color. Not easy by any means and often abused.

There are good reasons for all the varying shapes, sizes, lengths, and general details of brushes. Some artists have special brushes made for special purposes and sometimes they modify brushes, and all who are wise take wonderful care of their brushes.

Varnish will somewhat lessen the shine of brush marks, because it fills the interstices and flattens the surface. But varnish has its drawbacks, and just enough and no more than enough to lock up the picture should be the limit of its use.

Every student should acquaint himself with the qualities and uses of varnish by reading and comparing the books which deal specifically with the chemistry of painting.

The sweep of a brush should be so skilled that it will make the background behind a head seem to pass behind the head—not up to it—and make one know that there is atmosphere all around it.

The stroke that gives the spring of an eyelid or the flare of a nostril is wonderful because of its simplicity and certainty of intention.

There are brittle and scratchy strokes, lazy, maudlin, fatly made and phlegmatic strokes.

One of the worst is the miserly stroke.

Get the full swing of your body into the stroke.

Painting should be done from the floor up, not from the seat of a comfortable chair.

Have both hands free. One for the brush and the other for reserve brushes and a rag.

Rag is just as essential as anything else. Choose it well and have plenty of it in stock, cut to the right size.

In having the best use of your two hands the thumb palette is eliminated. Have a table, glass top, white or buff paper under the glass. Have a brush cleaner. Make it yourself. The things sold in shops are toys.

Get the habit of cleaning your brush constantly as you work. The rag to wipe it. Thus the brush can hold the kind of paint you need for the stroke.

Great results are attained by the pressure, force or delicacy with which the stroke is made.

The choice of brushes is a personal affair to be determined by experience.

Too many brushes, or too many sorts of brushes cause confusion. Have a broad stock, but don’t use them all at once.

It is remarkable how many functions one brush can perform.

Use not too many, but use enough.

“Some painters use their fingers. Look out for poison.”

Some painters use their fingers. Look out for poison. Some pigments are dangerous—any lead white, for instance.

Silk runs, is fluent, has speed, almost screams at times.

Cloth is slower, thicker, the stroke is slower, heavier.

Velvet is rich, caressing, its depths are mysterious, obscure. The stroke loses itself, not a sign of it is visible. So also the shadows in hair.

Strokes which move in unison, rhythms, continuities throughout the work; that interplay, that slightly or fully complement each other.

See pictures by Renoir.

Effects of perspective are made or defeated by sizes of strokes, or by their tonalities.

There are brush handlings which declare more about the painter than he declares about his subject. Such as say plainly: “See what vigor I have. Bang!” “Am I not graceful?” “See how painfully serious I am!” “I’m a devil of a dashing painter—watch this!”

Velasquez and Franz Hals made a dozen strokes reveal more than most other painters could accomplish in a thousand.

Compare a painting by Ingres with one by Manet and note the difference of stroke in these two very different men. The stroke is like the man. I prefer Manet of the two. But that is a personal matter. Both were very great artists.

Compare the paintings if they are within your reach, if not compare reproductions. Compare also Ingres’ drawings with those of Rembrandt.

Manet’s stroke was ample, full, and flowed with a gracious continuity, was never flip or clever. His “Olympia” has a supreme elegance.

Icy, cold, hard, brittle, timid, fearsome, apologetic, pale, negative, vulgar, lazy, common, puritanical, smart, evasive, glib, to add to the list and repeat a few. Strokes of the brush may be divided into many families with many members in each family. A big field to draw from and an abundant series of complements and harmonies among them; to use as units in the stress and strain of picture construction. Perhaps there is not a brush mark made that would not be beautiful if in its proper place, and it is the artist’s business to find the stroke that is needed in the place. When it is in its proper place, even though it bore one of the hateful names I have given some of them, it is transformed, and it has become gracious or strong and must be re-named.

2.

The picture that looks as if it were done without an effort may have been a perfect battlefield in its making.

A thing is beautiful when it is strong in its kind.

What beautiful designs a fruit vendor makes with his piles of oranges and apples. He takes much trouble and I am sure has great pleasure in arranging them so that you can see them at their best.

A millionaire will own wonderful pictures and hang them in a light where you can’t half see them. Some are even proud of the report, “Why, he has Corots in the kitchen— Daubignys in the cellar!”

If it is up to the artist to make the best pictures he can possibly make, it is up to the owners to present them to the very best advantage.

The good things grow better. There is always a new surprise each time you see them.

The man who has something very definite to say and tries to force the medium to say it will learn how to draw.

3.

Originality

Originality: Don’t worry about your originality. You could not get rid of it even if you wanted to. It will stick to you and show you up for better or worse in spite of all you or anyone else can do.

4.

An address to the students of the School of Design for Women, Philadelphia

Written in 1901

The real study of an art student is generally missed in the pursuit of a copying technique.

I knew men who were students at the Academie Julian in Paris, where I studied in 1888, thirteen years ago. I visited the Academie this year (1901) and found some of the same students still there, repeating the same exercises, and doing work nearly as good as they did thirteen years ago.

At almost any time in these thirteen years they have had technical ability enough to produce masterpieces. Many of them are more facile in their trade of copying the model, and they make fewer mistakes and imperfections of literal drawing and proportion than do some of the greatest masters of art.

These students have become masters of the trade of drawing, as some others have become masters of their grammars. And like so many of the latter, brilliant jugglers of words, having nothing worthwhile to say, they remain little else than clever jugglers of the brush.

The real study of an art student is more a development of that sensitive nature and appreciative imagination with which he was so fully endowed when a child, and which, unfortunately in almost all cases, the contact with the grown-ups shames out of him before he has passed into what is understood as real life.

Persons and things are whatever we imagine them to be.

We have little interest in the material person or the material thing. All our valuation of them is based on the sensations their presence and existence arouse in us.

And when we study the subject of our pleasure it is to select and seize the salient characteristics which have been the cause of our emotion.

Thus two individuals looking at the same objects may both exclaim “Beautiful!”—both be right, and yet each have a different sensation—each seeing different characteristics as the salient ones, according to the prejudice of their sensations.

Beauty is no material thing.

Beauty cannot be copied.

Beauty is the sensation of pleasure on the mind of the seer.

No thing is beautiful. But all things await the sensitive and imaginative mind that may be aroused to pleasurable emotion at sight of them. This is beauty.

The art student that should be, and is so rare, is the one whose life is spent in the love and the culture of his personal sensations, the cherishing of his emotions, never undervaluing them, the pleasure of exclaiming them to others, and an eager search for their clearest expression. He never studies drawing because it will come in useful later when he is an artist. He has not time for that. He is an artist in the beginning and is busy finding the lines and forms to express the pleasures and emotions with which nature has already charged him.

No knowledge is so easily found as when it is needed.

Teachers have too long stood in the way; have said: “Go slowly—you want to be an artist before you’ve learned to draw!”

Oh! those long and dreary years of learning to draw! How can a student after the drudgery of it, look at a man or an antique statue with any other emotion than a plumbob estimate of how many lengths of head he has.

One’s early fancy of man and things must not be forgot. One’s appreciation of them is too much sullied by coldly calculating and dissecting them. One’s fancy must not be put aside, but the excitement and the development of it must be continued through the work. From the antique cast there should be no work done if it is not to translate your impression of the beauty the sculptor has expressed. To go before the cast or the living model without having them suggest to you a theme, and to sit there and draw without a theme for hours, is to begin the hardening of your sensibilities to them—the loss of your power to take pleasure in them. What you must express in your drawing is not “what model you had,” but “what were your sensations,” and you select from what is visual of the model the traits that best express you.

In drawing from the cast the work may be easier. The cast always remains the same—the student has but to guard against his own digressions. The living model is never the same. He is only consistent to one mental state during the moment of its duration. He is always changing. The picture which takes hours—possibly months—must not follow him. It must remain in the one chosen moment, in the attitude which was the result of the sensation of that moment. Most students wade through a week of changings both of the subject and their own views of it. The real student has remained with the idea which was the commencement. He has simply used the model as the indifferent manikin of what the model was. Or, should he have given up the first idea, it was then to take on another, having destroyed the work which was the expression of the former.

The habit of digression—lack of continued interest— want of fixed purpose, is an almost general failing. It is too easy to drift and the habit of letting oneself drift begets drifting. The power of concentration is rare and must be sought and cultivated, and prolonged work on one subject must not be mistaken for concentration. Prolonged work on one subject may be simply prolonged digression, which is a useless effort, as it is to no end.

Your model can be little more than an indifferent manikin of herself. Her presence can but recall to you the self she was when she so inspired you. She can but mislead if you follow her. You need great time to paint your picture. It took her a moment, a glance, a movement, to inspire it. She may never be just as she was again. She changes momentarily. As she poses she may be in the anguish of fatigue. Who can stand all those hours, detained from their natural pursuits without being bored? At least there is a drifting of the mind, pleasant, gay, sad, trivial—and, imperceptibly the forms and the attitude change to the expression of the thought, and it gets into the brush of the careless artist and it comes out in the paint.

Few paintings express one idea. They are generally drifting composites wandering through the poses of many frames of mind of the sitter, and the easy driftings of the view of the artist. They present the subject, but the parts are as seen under different emotions, and their only excuse is that they are so wonderfully well done.

Why do we love the sea? It is because it has some potent power to make us think things we like to think.

A “still life” in great art is a living thing. The objects are painted for what they suggest, and their presentation has no excuse if it is not to carry to the mind of the observer the fancy they aroused in the artist. If they do not do this and are but simply wonderfully well copied, then there is no communication between the artist and the observer, and the latter gets no more than he would if he were to see the same things in nature. Chardin was a great painter of still life.

When a student comes before his model his first question should be: “What is my highest pleasure in this?” and then, “Why?” All the greatest masters have asked these questions—not literally—not consciously, perhaps. And with them this highest pleasure has grown until with their great imaginations, they have come to something like a just appreciation of the most important element of their subject, having eliminated its lesser qualities. With their prejudice for its greater meaning, their eyes take note only of the lines and forms which seem to be the manifestation of that greater meaning.

This is selection. And the result is extract.

The great artist has not reproduced nature, but has expressed by his extract the most choice sensation it has made upon him.

A teacher should be an encourager.

An artist must have imagination.

An artist who does not use his imagination is a mechanic. No material thing is beautiful.

All is as beautiful as we think it.

There is a saying that “love is blind”—perhaps the young man is the only one who appreciates her.

There are many artists who cast upon the floor and trample under foot their very best production simply because it was done hurriedly under the inspiration of an idea; the work has expressed the idea, but remains otherwise incomplete, “unfinished” they say, and then they save and frame and put under glass a work that is but a clever composite of a series of incomplete ideas, seemingly finished. The latter has taken time, work, study, looks knowing, shows erudition. There has been no shirking. They call it serious—and serious it is.

The other is but a butterfly of the imagination. However, butterflies are beautiful.

Such a proposition as this should not send art students off to the making of hasty dashes at ideas and end in reducing art to a scribble or two, for there is a check to that in the works of most of the masters. There are the old Dutch, whose butterflies lived through the most completed development, as well as those of such as Whistler, which may have been done with the least amount of detail. All are complete. Each beautiful in its kind.

An art student should read, or talk a great deal with those who have read. His conversations with his intimate fellow-students should be more of his life and less of paint.

He should be careful of the influence of those with whom he consorts, and he runs a great risk in becoming a member of a large society, for large bodies tend toward the leveling of individuality to a common consent, the forming and the adherence to a creed. And a member must be ever in unnecessary broil or pretend agreement which he cannot permit himself to do, for it is his principle as an art student to have and to defend his personal impressions. Somebody, I think it was Corot, said that art is “nature as seen through a temperament.”

There are, however, societies of a very few—little cliques which form by sympathy and which believe in and sustain the independence of their members, and which live by the variety of individualities expressed. Such was that coterie of which Manet, Degas, Monet, Whistler and others of special distinction were the outcome. Rossetti, Burne-Jones, the pre-Raphaelites, formed another. Many are the little congresses among the students in Paris made up of men from all countries, who draw together through similar sympathy.

The reproduction of things is but the idle industry of one who does not value his sensations, and who was done with his imaginings when he passed out of childhood and consented that the prancing horse he had bestrode in those happy days had only been a broken broomstick.

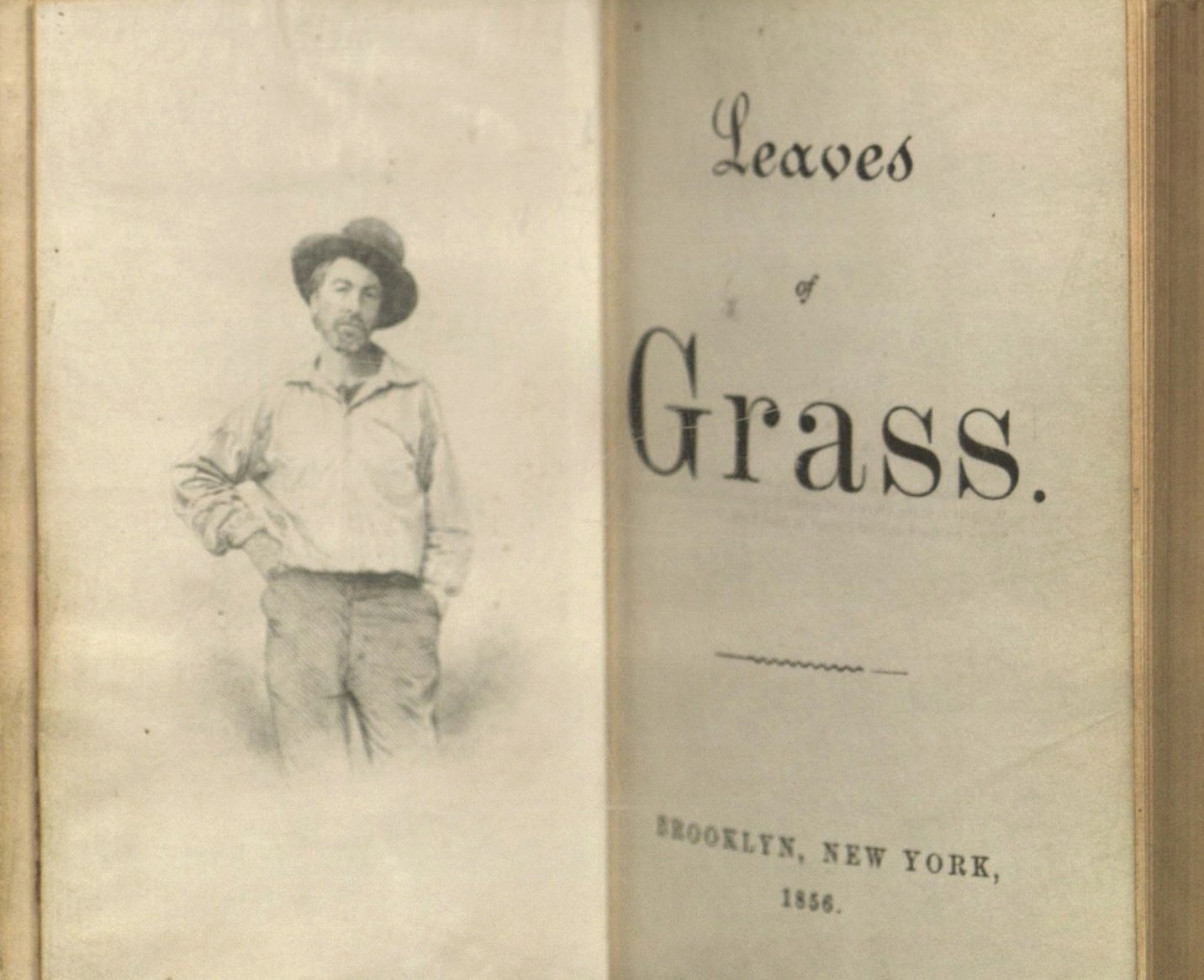

Old Walt Whitman, to his last days, was as a child in the gentleness and the fullness of his fancy. A few flowers on his window-sill were enough to arouse in him the pleasantest sensations and the most prophetic philosophy.

Walt Whitman was such as I have proposed the real art student should be. His work is an autobiography—not of haps and mishaps, but of his deepest thought, his life indeed.

No greater treasure can be given us. Confessions like those of Rousseau or those of Marie Bashkirtseff are thin in comparison with this life expressed by Whitman, which is so beautiful, in the reading of which we find ourselves.

Whitman died a few years ago, but Whitman lives on in his work, which is his life, and which will expand and be greater the more it is known. Like Shakespeare, who met so few in his fifty odd years, and knew us all so well down to this day. Think of the brilliant writers whose touches on the hearts of their publics have not lasted out even their own lifetimes.

Permit me to quote these lines of Walt Whitman’s, written of his own work:—

“‘Leaves of Grass,’ indeed (I cannot too often reiterate) has mainly been the outcropping of my own emotional and other personal nature—an attempt from first to last, to put a person, a human being (myself, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, in America) freely, fully and truly on record. I could not find any similar personal record in current literature that satisfied me. But it is not on ‘Leaves of Grass’ distinctively as literature, or a specimen thereof, that I feel to dwell or advance claims. No one will get at my verses who insists upon viewing them as a literary performance, or attempt at such performance, or as aiming mainly towards art or aestheticism,” and then close at hand he quotes from another. A picture of unknown authorship is the subject. “Rubens, asked by a pupil to name the school to which the picture belongs, replies, ‘I do not believe the artist, unknown and perhaps no longer living who has given the world this legacy, ever belonged to any school or ever painted anything but this one picture, which is a personal affair—a piece out of a man’s life.’”

And he quotes from Taine:—

“‘All original art is self-regulated; and no original art can be regulated from without. It carries its own counterpoise and does not receive it from elsewhere—lives on its own blood.’”

One of the great difficulties of an art student is to decide between his own natural impressions and what he thinks should be his impressions. When the majority of students and the majority of so-called arrived artists go out into landscape, saying they intend to look for a “motive,” they too often mean, unconsciously enough, that it is their intention to look until they have found an arrangement in the landscape most like someone of the pictures they have seen and liked in the galleries. A hundred times, perhaps, they have walked by their own subject, felt it, enjoyed it, but having no estimate of their own personal sensations, lacking faith in themselves, pass on until they come to this established taste of another. And here they would be ashamed if they did not appreciate, for this is an approved taste, and they try to adopt it because it is what they think they should like whether they really do so or not.

Is it not fine to see the development of oneself? The finding of one’s own tastes. The final selection of a most favorite theme; the concentration of all one’s forces on that theme; its development; the constant effort to find its clearest expression in the chosen medium; an effort of expression which commenced with the beginning of the idea, and follows its progress step by step, becoming a technique born of the theme itself and special to it. The continuation through years, new elements entering as life goes on, each step differing, yet all the same. A simple theme on which a life is strung.

The study of art should go broadcast.

Every individual should study his own individuality to the end of knowing his tastes. Should cultivate the pleasures so discovered and find the most direct means of expressing those pleasures to others, thereby enjoying them over again.

Art after all is but an extension of language to the expression of sensations too subtle for words.

And we will acquire this greater power of revealing ourselves!

All the forms of art are to be a common language, and the artist will no longer distinguish himself by his tricks of painting, but must take rank only by the weight and the beauty of what he expresses with the wise use of the languages of art universally known.