The Art Spirit By Robert Henri

Chapter 10

The Art Spirit

Robert Henri

Chapter 10

Appreciation of life

“My People”

1.

Appreciation of life is not easy. One says he must earn a living—but why? Why live? It seems as though a great many who do earn the living or have it given them do not get much out of it. A sort of aimless racing up and down in automobiles, an aimless satisfaction in amassing money, an aimless pursuit of “pleasure,” nothing personal, all external. I have known people who have sat for years in the cafés of Bohemia, who never once tasted of that spirit which has made life in Bohemia a magnet. These people were not in Bohemia—they were simply present. Really bored to death although they did not know it, and poisoned too by the food and drink—being inert they were open prey to it. They and their kind, in the various ways, are in hot pursuit of something they are not fitted to attain. It takes wit, and interest and energy to be happy. The pursuit of happiness is a great activity. One must be open and alive. It is the greatest feat man has to accomplish, and spirits must flow. There must be courage. There are no easy ruts to get into which lead to happiness. A man must become interesting to himself and must become actually expressive before he can be happy. I do not say that these people are devoid of the possibility of happiness, but they have not been enough interested in their real selves to have awareness of the road when they are on it. They no doubt fall into moments of supreme pleasure, which they enjoy, whether consciously or unconsciously. It is these moments which I am sure prevent them from suicide. There are, however, others who do recognize their great moments, and who go after them with all their strength.

Walt Whitman seems to have found great things in the littlest things of life.

It beats all the things that wealth can give and everything else in the world to say the things one believes, to put them into form, to pass them on to anyone who may care to take them up.

There is the hope of happiness—a hope of development, that some day we may get away from these self-imposed dogmas and establish something that will make music in the world and make us natural.

Of course, if a man were to plump suddenly into the world with the gift of telling the actual truth and acting rightly, he would not fit into our uncertain state, he would certainly be very disturbing—and most probably we would send him to jail.

We haven’t arrived yet, and it is foolish to believe that we have. The world is not done. Evolution is not complete.

2.

“My People”

Article in The Craftsman, 1915.

The people I like to paint are “my people,” whoever they may be, wherever they may exist, the people through whom dignity of life is manifest, that is, who are in some way expressing themselves naturally along the lines nature intended for them. My people may be old or young, rich or poor, I may speak their language or I may communicate with them only by gestures. But wherever I find them, the Indian at work in the white man’s way, the Spanish gypsy moving back to the freedom of the hills, the little boy, quiet and reticent before the stranger, my interest is awakened and my impulse immediately is to tell about them through my own language—drawing and painting in color.

I find as I go out, from one land to another seeking “my people,” that I have none of that cruel, fearful possession known as patriotism; no blind, intense devotion for an institution that has stiffened in chains of its own making. My love of mankind is individual, not national, and always I find the race expressed in the individual. And so I am “patriotic” only about what I admire, and my devotion to humanity burns up as brightly for Europe as for America; it flares up as swiftly for Mexico if I am painting the peon there; it warms toward the bullfighter in Spain, if, in spite of its cruelty, there is that element in his art which I find beautiful; it intensifies before the Irish peasant, whose love, poetry, simplicity and humor have enriched my existence, just as completely as though each of these people were of my own country and my own hearthstone. Everywhere I see at times this beautiful expression of the dignity of life, to which I respond with a wish to preserve this beauty of humanity for my friends to enjoy.

This thing that I call dignity in a human being is inevitably the result of an established order in the universe. Everything that is beautiful is orderly, and there can be no order unless things are in their right relation to each other. Of this right relation throughout the world beauty is born. A musical scale, the sword motif for instance in the Ring, is order in sound; sculpture as the Greeks saw it, big, sure, infinite, is order in proportion; painting, in which the artist has the wisdom that ordained the rainbow is order in color; poetry—Whitman, Ibsen, Shelley, each is supreme order in verbal expression. It is not too much to say that art is the noting of the existence of order throughout the world, and so, order stirs imagination and inspires one to reproduce this beautiful relationship existing in the universe, as best one can. Everywhere I find that the moment order in nature is understood and freely shown, the result is nobility;—the Irish peasant has nobility of language and facial expression; the North American Indian has nobility of poise, of gesture; nearly all children have nobility of impulse. This orderliness must exist or the world could not hold together, and it is a vision of orderliness that enables the artist along any line whatsoever to capture and present through his imagination the wonder that stimulates life.

It is disorder in the mind of man that produces chaos of the kind that brings about such a war as we are today over-whelmed with. It is the failure to see the various phases of life in their ultimate relation that brings about militarism, slavery, the longing of one nation to conquer another, the willingness to destroy for selfish unhuman purposes. Any right understanding of the proper relation of man to man and man to the universe would make war impossible.

The revolutionary parties that break away from old institutions, from dead organizations are always headed by men with a vision of order, with men who realize that there must be a balance in life, of so much of what is good for each man, so much to test the sinews of his soul, so much to stimulate his joy. But the war machine is invented and run by the few for the few. There is no order in the seclusion of the world’s good for the minority, and the battle for this proves the complete disorganization of the minds who institute it. War is impossible without institutionalism, and institutionalism is the most destructive agent to peace or beauty. When the poet, the painter, the scientist, the inventor, the laboring man, the philosopher, see the need of working together for the welfare of the race, a beautiful order will be the result and war will be as impossible as peace is today.

Although all fundamental principles of nature are orderly, humanity needs a fine, sure freedom to express these principles. When they are expressed freely, we find grace, wisdom, joy. We only ask for each person the freedom which we accord to nature, when we attempt to hold her within our grasp. If we are cultivating fruit in an orchard, we wish that particular fruit to grow in its own way; we give it the soil it needs, the amount of moisture, the amount of care, but we do not treat the apple tree as we would the pear tree or the peach tree as we would the vineyard on the hillside. Each is allowed the freedom of its own kind and the result is the perfection of growth which can be accomplished in no other way. The time must come when the same freedom is allowed the individual; each in his own way must develop according to nature’s purpose, the body must be but the channel for the expression of purpose, interest, emotion, labor. Everywhere freedom must be the sign of reason.

We are living in a strange civilization. Our minds and souls are so overlaid with fear, with artificiality, that often we do not even recognize beauty. It is this fear, this lack of direct vision of truth that brings about all the disaster the world holds, and how little opportunity we give any people for casting off fear, for living simply and naturally. When they do, first of all we fear them, then we condemn them. It is only if they are great enough to outlive our condemnation that we accept them.

Always we would try to tie down the great to our little nationalism; whereas every great artist is a man who has freed himself from his family, his nation, his race. Every man who has shown the world the way to beauty, to true culture, has been a rebel, a “universal” without patriotism, without home, who has found his people everywhere, a man whom all the world recognizes, accepts, whether he speaks through music, painting, words or form.

Each genius differs only from the mass in that he has found freedom for his greatness; the greatness is everywhere, in every man, in every child. What our civilization is busy doing, mainly, is smothering greatness. It is a strange anomaly; we destroy what we love and we reverence what we destroy. The genius who is great enough to cut through our restraint wins our applause; yet if we have our own way we restrain him. We build up the institution on the cornerstone of genius and then we begin to establish our rules and our laws, until we have made all expression within the commonplace. We build up our religion upon the life of the freest men that ever lived, the men who refused all limitations, all boundaries, all race kinship, all family ties; and then we circumscribe our religion until the power that comes from the organization blinds and binds its adherents. We would circumscribe our music, we would limit the expression of our painter, we would curb our sculpture, we would have a fixed form for our poet if we could. Fortunately, however, the great, significant, splendid impulse for beauty can force its way through every boundary. Wagner can break through every musical limitation ever established, Rodin can mold his own outline of the universe, Whitman can utter truths so burning that the edge of the sonnet, roundelay, or epic is destroyed, Millet meets his peasant in the field and the Academy forgets to order his method of telling the world of this immemorial encounter.

I am always sorry for the Puritan, for he guided his life against desire and against nature. He found what he thought was comfort, for he believed the spirit’s safety was in negation, but he has never given the world one minute’s joy or produced one symbol of the beautiful order of nature. He sought peace in bondage and his spirit became a prisoner.

Technique is to me merely a language, and as I see life more and more clearly, growing older, I have but one intention and that is to make my language as clear and simple and sincere as is humanly possible. I believe one should study ways and means all the while to express one’s idea of life more clearly. The language of color must of necessity vary. There are great things in the world to paint, night, day, brilliant moments, sunrise, a people in the joy of freedom; and there are sad times, half-tones in the expression of humanity, so there must be an infinite variety in one’s language. But language can be of no value for its own sake, it is so only as it expresses the infinite moods and growth of humanity. An artist must first of all respond to his subject, he must be filled with emotion toward that subject and then he must make his technique so sincere, so translucent that it may be forgotten, the value of the subject shining through it. To my mind a fanciful, eccentric technique only hides the matter to be presented, and for that reason is not only out of place, but dangerous, wrong.

All my life I have refused to be for or against parties, for or against nations, for or against people. I never seek novelty or the eccentric; I do not go from land to land to contrast civilizations. I seek only, wherever I go, for symbols of greatness, and as I have already said, they may be found in the eyes of a child, in the movement of a gladiator, in the heart of a gypsy, in twilight in Ireland or in moonrise over the deserts. To hold the spirit of greatness is in my mind what the world was created for. The human body is beautiful as this spirit shines through, and art is great as it translates and embodies this spirit.

“All my life I have refused to be for or against parties, for or against nations, for or against people.”

— Robert Henri

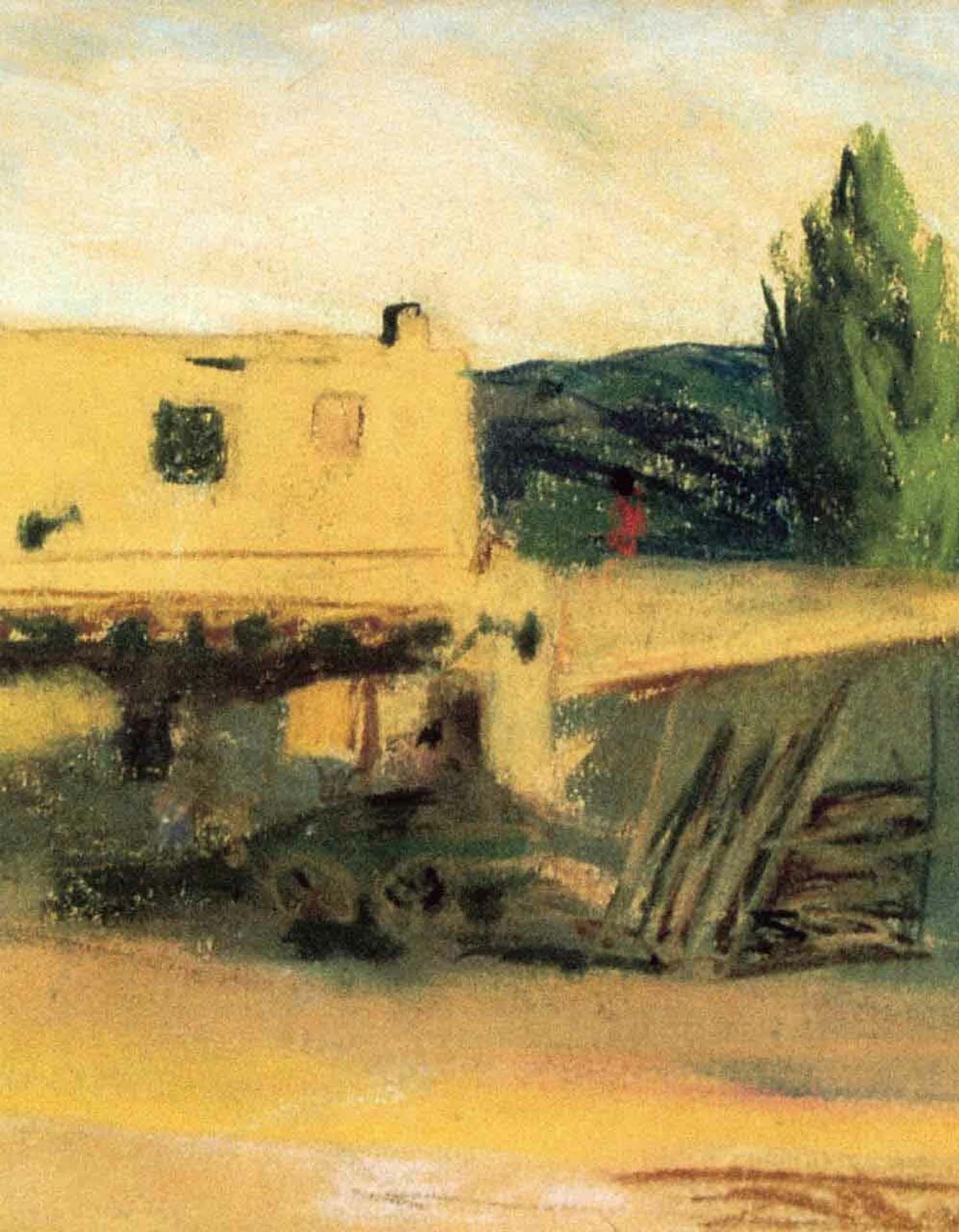

New Mexican Landscape, by Robert Henri

Since my return from the Southwest, where I saw many great things in a variety of human forms—the little Chinese-American girl, who has found coquetry in new freedom; the peon, a symbol of a destroyed civilization in Mexico, and the Indian who works as one in slavery and dreams as a man in still places—I have been reproached with not adding to my study of these people the background of their lives. This has astonished me because all their lives are in their expressions, in their eyes, their movements, or they are not worth translating into art. I was not interested in these people to sentimentalize over them, to mourn over the fact that we have destroyed the Indian, that we are changing the shy Chinese girl into a soubrette, that our progress through Mexico leaves a demoralized race like the peons. This is not what I am on the outlook for. I am looking at each individual with the eager hope of finding there something of the dignity of life, the humor, the humanity, the kindness, something of the order that will rescue the race and the nation. That is what I have wanted to talk about and nothing else. The landscape, the houses, the workshop of these people are not necessary. I do not wish to explain these people, I do not wish to preach through them, I only want to find whatever of the great spirit there is in the Southwest. If I can hold it on my canvas I am satisfied, for after all, every race, every individual in the race must develop as nature intended or become extinct. These things belong to the power of the ages. I am only seeking to capture what I have discovered in a few of the people. Every nation in the world, in spite of itself, produces the occasional individual that does express in some sense this beauty, with enough freedom for natural growth. It is this element in people which is the essence of life, which springs out away from the institution, which is the reformation upon which the institution is founded, which laughs at all boundaries and which in every generation is the beginning, the birth of new greatness, which holds in solution all genius, all true progress, all significant beauty.

It seems to me that this very truth accounts for the death of religions. The institutionalized religion doubts humanity, whereas truth itself rests upon faith in humanity. The minute we shut people up we are proving our distrust in them; if we believe in them we give them freedom, and through freedom they accomplish, and nothing else matters in the world. We harness up the horse, we destroy his very race instincts, and when we want a thrill for our souls we watch the flight of the eagle. This has been true from the beginning of time. It is better that every thought should be uttered freely, fearlessly, than that any great thought should be denied utterance for fear of evil. It is only through complete independence that all goodness can be spoken, that all purity can be found. Even indecency is bred of restriction not of freedom, for how can the spirit which controls the ethical side of life be trusted except through the poise that is gained by exercise? When we think honestly, we never desire individuals bound hand and foot, and the ethical side of man’s nature we cannot picture as overwhelmed and smothered with regulations if we are to have a permanent human goodness; for restrictions hide vice, and freedom alone bears morality.

I wonder when, as a nation, we shall ever learn the difference between freedom and looseness, between restriction and destruction,—so far we certainly have not. When people have the courage to think honestly, they will live honestly, and only through transparent honesty of life will a new civilization be born. The people who think and live sincerely will bear children who have a vision of the truth, children living freely and beautifully. We must have health everywhere if we are to overcome such civilizations as we see falling to pieces today, not only health of body, but health of mind. Humanity today is diseased, it is proving itself diseased in murder, fire, hideous atrocity.

The more health we have in life the fewer laws we will have, for health makes for happiness and laws for the destruction of both. If as little children, we were enabled to find life so simple, so transparent that all the beautiful order of it were revealed to us, if we knew the rhythm of Wagner, the outline of Pericles, if color were all about us beautifully related, we should acquire this health and have the vision to translate our lives into the most perfect art of any age or generation.

I sometimes wonder what my own work would have been if I could as a child have heard Wagner’s music, played by great musicians. I am sure the rhythm of it would have influenced my own work for all time. If in addition to this great universal rhythm, I could have been surrounded by such art as Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, where he paints neither religion nor paganism, but that third estate which Ibsen suggests “is greater than what we know”; if these things had been my environment, I feel that a greater freedom of understanding and sympathy would have come to me. Freedom is indeed the great sign which should be written on the brow of all childhood.

There are other things I should like to speak of which have been important to me as a painter. In addition to a sense of freedom, a sure belief that only the very essence of the universe was worth capturing and holding, perhaps one of the most valuable things for the painter to study is economy, which is necessary in every phase of life, almost the most valuable asset a man can possess. But in painting especially, a man should learn to select from all experience, not only from his own but from that of all ages, essential beauty. He should learn through wisdom to gather for his work only the vital and express that with the keenest delight and emotion. The art that has lasted through all ages has been culled in this way from often what seemed meagre opportunity. Beethoven must have captured his Ninth Symphony only through the surest understanding of what was essential to hold and translate to the world. He was not listening carelessly or recklessly to the melody which is held on the edge of the infinite for the man with spiritual ears; rather he was eager, intense, sure, wise and economical as he gathered beauty and distilled it into that splendid harmony which must forever hold the world captive. And so all great music, great prose, everything beautiful must depend upon the sure, free measure with which it is garnered and put into language for the people, for each lovely thing has its intrinsic value and belongs in its own position for the world to study, understand and thrive upon.

In various ways the free people of the world will find and translate the beauty that exists for them; the musician most often in the hidden space of the world, the sculptor closer to nature, feeling her forms, needing her inspiration; the poet from the simple people in remote countries; the painter it seems to me, mainly from all kinds and conditions of people, from humanity in the making, in the living. Each man must seek for himself the people who hold the essential beauty, and each man must eventually say to himself as I do, “these are my people and all that I have I owe to them.”

“these are my people and all that I have I owe to them.”

— Robert Henri